One hundred years ago, in 1905, Elkan Naumburg saw the need of presenting free symphonic concerts in Central Park. As a result, the concerts that bear his name have been performed there almost without interruption ever since. In 1924 the New York Times wrote:

Mr. Naumburg was the first, and for many years the only patron of music to give free concerts in the Parks to the people of New York, defraying all the expense and supervising all the details, including the selection of programs and soloists.

Originally the concerts did not have a board of trustees, Elkan just underwrote the costs. Initially, and for many years, concerts were principally provided on national holidays. By 1916, the New York Times began to describe the events as Naumburg Concerts. In 1922, a board was formed to run the concerts. Tellingly, its name was the People’s Music Foundation. However, in 1958, the current title of Naumburg Orchestral Concerts was settled upon. Worries about its communist sounding name, generated by the concert’s legal counsel, long-standing board member and family friend Peter H. Weil, may have encouraged the change. Or, as a letter of January 1959 from Walter W. Naumburg states, it was merely the result of now having seven Naumburg family members on the Concerts board. In any case, after 1924, Elkan’s memory was always specifically honored in the concert program’s musical choices and notes. Each year’s series also marked his death date with a special concert. In more recent times this custom has been abandoned, along with a change to mostly weekday concerts.

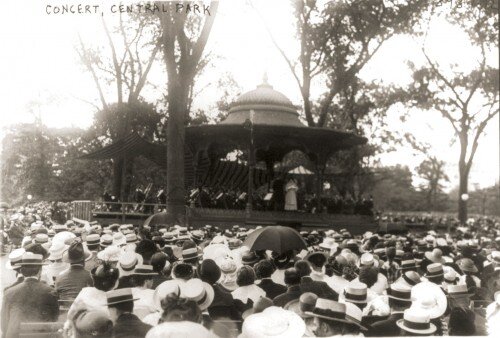

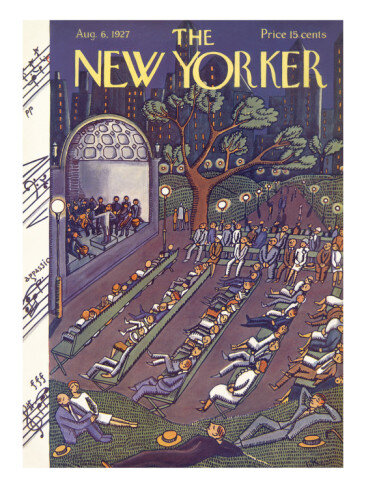

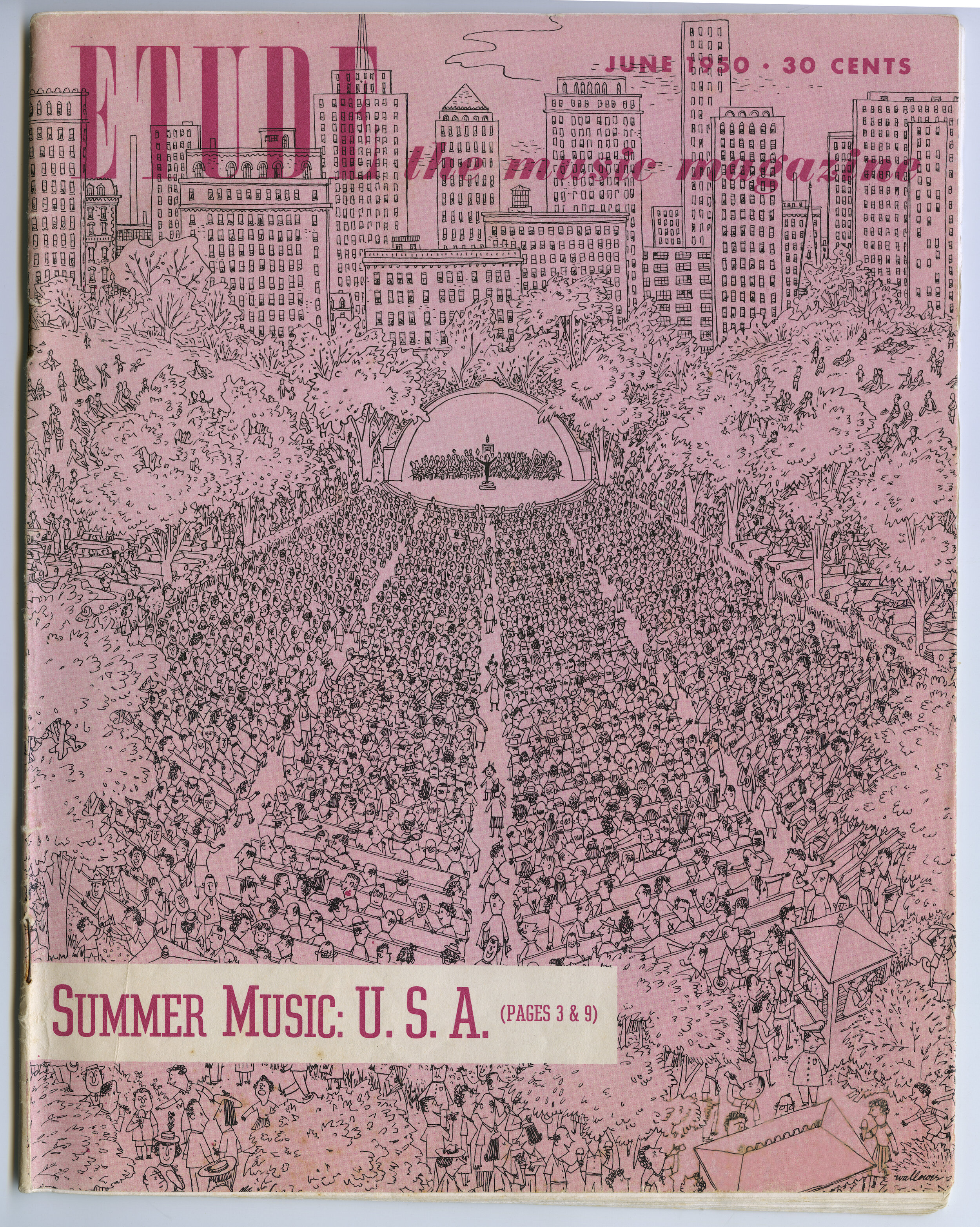

The Naumburg Concerts in Central Park were patterned after earlier musical performances, which date to the earliest days of Central Park. In 1859 Jacob Wrey Mould, an amateur musician and the architect who designed many of the original structures in Central Park, persuaded his wealthy friends to pay for free band concerts at a temporary bandstand in the Ramble, and he arranged their musical programs. The first concert, on July 13, included the Festival March from Tannhäuser, Mendelssohn’s song, “I would that my Love,” selections from La Traviata and Strauss’s Sorgenbrecher Waltz. The concerts were transferred to the Mall in the summer of 1860, and the New York Herald reported the September 22 concert attracted: at least five thousand persons gathered around the performers, while outside of these were stationed an immense number of carriages…filled with the beauty and fashion of New York.

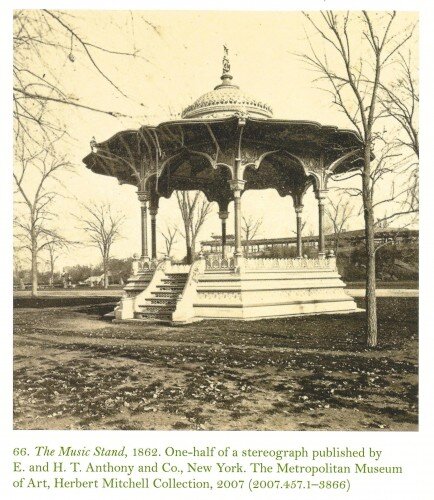

The overwhelming popularity of the concerts prompted Central Park’s board to finance them and to build a permanent bandstand on the west side of the Mall near the Terrace. Mould designed the elaborately painted and brightly gilded Moorish-style wooden and cast-iron structure, completed in 1862. By 1874, these immensely popular concerts were largely sponsored by the Parks department, later by various City administrative groups (Police, Fire, Street Cleaning), and finally in the 1920’s by the Goldman Band underwritten by the public and/or solely by the Daniel and Murry Guggenheim families (1924 & likely other years):

—The Mall, Central Park—

Saturday, May 23, 1874

The double rows of American Elms, planted fourteen years earlier, create a green tunnel. Sunlight filters through the canopy of new leaves and throws dappled patterns of light and shade on the gravel walk. It is a beautiful day, the Mall is crowded: ladies in voluminous skirts and colorful hats; Irish nurses in bonnets and white aprons, pushing baby carriages; gentlemen in frock coats and top hats; a few young clerks in stylish broadcloth suits; the children in a variety of dress, miniature versions of their parents. It is a decorous crowd; tomorrow-Sunday-is when working people have a holiday and attendance will be even larger.

At the north end of the Mall, on the west side, is the bandstand. Mould has pulled out all the stops for this design. The raised platform is covered by a Moorish-style cupola, dark blue and covered with gilt stars. It is topped by a sculpture of a lyre. The roof is supported by crimson cast-iron columns. The bandstand is unoccupied- the Saturday-afternoon concerts start next month. The annual summer series is so popular- up to forty-five thousand people attend -that the park board has provided extra seating and has taken the unprecedented step of allowing listeners to sit on the grass. Not everyone admires these free concerts. “The barriers and hedges of society for the time being are let down,” sniffs the Times, “unfortunately also a few of its decencies are forgotten.”

The barriers of society are not altogether absent. Across the Mall from the bandstand is a broad concourse where the wealthy park their carriages and, separated from the lower orders by a long wisteria arbor, listen to the music in comfortable isolation. Beside the concourse stands a large one-story building with a swooping tiled roof and deep overhanging eaves. Originally the Ladies Refreshment Stand, it has recently been converted into a restaurant called the Casino.

An excerpt from Witold Rybczynski’s A Clearing in the Distance, 1999, pp.317-18 in which a letter, of Frederick Law Olmsted, a principal designer of Central Park, is quoted.

* * *

For its first eighteen years, the Naumburg Concerts were performed in this bandstand, near the center of the Concert Ground, just slightly off to the west of the Mall’s main axis. The audience encircled the Bandstand. Programs featured gems from Italian opera, or Strauss waltzes, selected symphonic movements, and short arias performed by talented young vocalists. This suited the musical taste of the time, when phonograph records of the Rosary, Humoresque, Road to Mandalay and Melody in F were found in every home.

Elkan Naumburg was born in Bavaria on January 1, 1835. He was already well grounded in his knowledge of music when he came to America on a clipper ship in 1850, age 15. After his arrival in Baltimore, Elkan worked in his brother-in-law’s dry goods business. His natural taste and love for music compelled him to save his hard earned money so that he might buy tickets to hear artists like Henri Vieuxtemps and Sigismund Thalberg. Soon, he also became acquainted with musicians that exposed him to chamber music in America. Though he related sending money home to his mother during these early years of his life, in the ‘September 29th 1923 Concert Program’ for the opening of the Naumburg Bandshell, he also confessed that he still had a feeling of disappointment because he missed hearing Jenny Lind. He could not raise the $7 needed for a ticket. Perhaps this impelled him to move on? For in 1853, age 18, Elkan left Baltimore for New York. There he established a clothing-manufacturing firm that was developed into one of the largest in the United States. Family lore has it that his firm’s specialty was a ready-to-wear ‘Sunday Best’ suit, newly popular in nineteenth-century America.

In New York, Elkan soon became warm friends of two rival conductors of the time, Theodore Thomas and Leopold Damrosch. Richard Arnold and Damrosch often played violin in string quartets at the Naumburg home. Elkan and Damrosch devised the Oratorio Society of New York in his 23rd Street home’s ‘back parlor’ in 1873. Elkan’s wife, Bertha Wehle Naumburg, thought of the name, and the group still exists. Louise Whitfield Carnegie, one of the Oratorio Society members, desired a hall to offer their concerts in. When she married her husband Andrew Carnegie, (1887), they went on to conceive and underwrite finance of its construction (1891). William B. Tuthill, the hall’s architect, was a talented cellist and a singer in church choirs with his organist wife. He then became a board member, and the secretary and manager of the Oratorio Society for 36 years. His studies to prepare for his work as Carnegie Hall’s architect also established him as an accomplished acoustician.

The Naumburg home soon also became a meeting place for celebrities in the operatic and concert worlds. Edward (Ned) Naumburg Jr. — Elkan’s nephew — especially remembered Elkan mentioning that he had entertained Mme. Marcella Sembrich, the renowned soprano of the time, and critics and musicologists like Henry T. Finck and Henry Krehbiel. With Andrew Carnegie, E. Francis Hyde and James Loeb, Naumburg also defrayed the expense of bringing several European conductors to New York for the Philharmonic concerts, among them Tiedler and Baumgartner, Vassily Ilich Safonof and Édouard Colonne, Henry Wood and Willem Mengelberg, none of whom had ever previously appeared before American audiences.

In 1905 Elkan Naumburg began his free Central Park concert series. They are quite likely patterned upon conversations Elkan had when he hosted and funded the visit of British conductor Sir Henry Joseph Wood CH, founder of the London Prom concerts in (1895) on Wood’s (1903-04) visit to NYC. His son Walter’s unpublished memoir specifically mentions that Elkan and Walter accommodated Wood and his wife, a Russian Princess, for their visit to New York while Wood conducted. Walter also recounts a story during Elkan and Walter’s entertainment of them to dinner one evening, in the family’s 48 West 58th Street home. Yet, Elkan was particularly focused upon the democratization of access to music, whereas access to all Prom concerts require ticket purchases.

The Naumburg Bandshell’s opening ‘September 29th 1923 Concert Program’ goes on to describe:

Elkan was among the founders of the Institute of Musical Arts. He established the first scholarship in the Agnes Scott College, an institution whose endowed scholarship funds have been an enduring benefit to music. He was a subscriber to the Philharmonic since 1863, and is one of the few laymen elected to honorary membership, and thus associated with Rubinstein, Liszt, Vieuxtemps and Thalberg and other renowned artists…. Mr. Naumburg’s home has long been a music lovers’ shrine. Weekly chamber music sessions have continued for about fifty years, and the late concert master of the Philharmonic, Mr. Richard Arnold, played the first violin there for over forty-five years. Mr. Leopold Damrosch, at Mr. Naumburg’s house, played first violin in quartette music on Sunday evenings.

Elkan founded a music scholarship at Harvard to provide a year’s study in Europe, and he was the largest contributor to the Bohemian Music Fund, which helped care for musicians in need. His early involvement with the nascent New York Philharmonic, also led him to found its first pension fund in 1890. That year Elkan also took a ‘family box’ at Carnegie Hall, which the family enjoyed at least until Walter died in 1959. The Naumburg’s also went on to serve on Carnegie Hall’s board for many years, through the 1970’s.

Further connections to Carnegie Hall also developed in the Naumburg family, just after Elkan’s death in 1924. His daughter-in-law, Mrs. George W. Naumburg [born Ruth Morgenthau] was a daughter of Ambassador Henry Morgenthau. Her father was a real-estate investor, business partner and uncle of Robert E. Simon (1877-1935) and then his son Robert E. Simon Jr. (1914-2015) through Pauline Morgenthau (1848-1915) Henry Morgenthau’s older sister. The Simon’s (and perhaps Morgenthau initially) as a family and a Real Estate firm, owned Carnegie Hall from 1925 to 1961. It was then sold by Robert E. Simon Jr. to help finance the purchase and construction of Reston, VA, a groundbreaking planned model town, in the pattern of his father’s pioneering planned community Radburn, NJ. The sale was also forced, or greatly advanced, by the construction of Lincoln Center, which had undermined both the hall’s profitability and the mere costs of maintaining it. The name Reston derives from Robert E. Simon’s town.

In 1890 Elkan’s eldest son, Walter, joined his father’s mercantile business. Walter had recently graduated from Harvard (1889 cum laude). But three years later, age 58, Elkan retired and Walter left the family’s manufacturing business. Wealthy, and already serving as a director of the Citizens Central Bank, from 1879 to 1909, Elkan was then approached by various friends who sought to borrow money from him. So, in 1893, Elkan and Walter founded and became partners in E. Naumburg & Co., a Wall Street banking house. George W. Naumburg, Elkan’s second and last child, Harvard (1898), soon followed in his elder brother’s footsteps. The firm specialized in commercial paper and financial fields:

The name became one of the most admired in banking. ‘It stood for absolute ability and integrity,’ recalls one collateral relative. ‘The Naumburg name could open any door.’ Such admiration brought success: in 1918 alone the firm sold some $325,000,000 worth of commercial paper…. Our chief rival was Goldman, Sachs. (The New Yorker, December 7, 1957 pp. 42-44)

Though 1918 may have been a particularly good year, it still provides an idea of the firm’s business acumen and significance. One of the largest commercial paper firms of its day, E. Naumburg & Co. of 14 Wall Street closed at year’s end 1931, when Shields & Co purchased it.

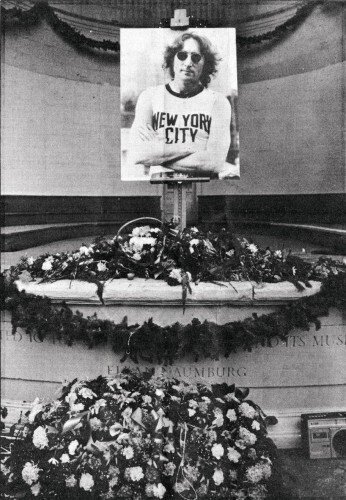

In 1924, the year of Elkan’s death, an elaborate orchestral concert was performed on September 14th, to honor his memory. Mayor John F. Hylan spoke and 30,000 people attended the service. The Mayor read and expanded upon his previously published eulogy:

When the eyes of Elkan Naumburg closed in final slumber the City of New York lost a philanthropic and a distinguished citizen. His death will be felt deeply by all who are interested in civic advancement, particularly the democratization of music. … With the same intensity which characterized his business activities, he applied himself to the task of bringing the benedictions and blessings of music to the great masses of the people. He arranged and financed the system of free musical concerts which are a conspicuous feature of our municipal life. Continuing his benevolence, he paid for and had constructed a new bandstand at the Mall in Central Park, a structure which he considered the supremely artistic achievement in this direction. Mr. Naumburg had both the capacity and resources to carry out his plans for the betterment of humanity. He applied himself to the task with generosity and diligence. His was the determination to build up the welfare of his less fortunate brethren. The fields of free musical entertainment and philanthropic endeavor in the City of New York will ever be identified with the name of Elkan Naumburg. Civic progress bows in respect to the memory of the citizen whose tireless activity and unstinted generosity have left their impress for good upon the material and spiritual phases of metropolitan life.

– The New York Times, August 2, 1924

Whereas, In the death of Elkan Naumburg this community sustains the loss of a public-spirited citizen whose beneficial activities were especially devoted to the development of the people’s interest in art and the finer things, particularly the art of music, and whose manifestations of this benevolence were so largely shown in connection with free concerts in the public parks and in the presentation of a stately and beautiful band stand in Central Park, therefore, be it

Resolved, That the Park Board of the City of New York respectfully extends to the family of the late Elkan Naumburg their sympathy and condolence in the grief and bereavement that is shared by many thousands of their fellow citizens.

– The Park Board of the City of New York

* * *

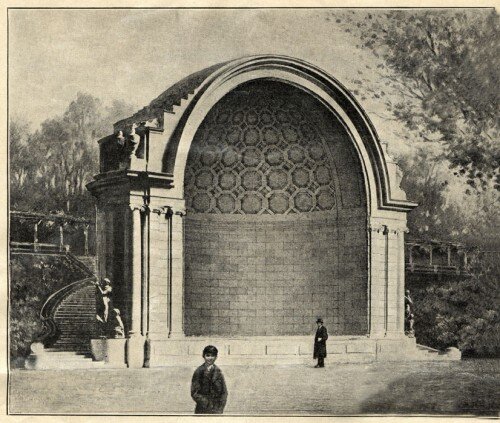

Designed in 1916, the Naumburg Bandshell was not built and opened until September 29, 1923. The delay was caused by Elkan, who thought it inappropriate to commence construction of a structure devoted to pleasure during or just after the First World War. The present design followed an earlier rejected proposal of Carrère & Hastings. That scheme was found wanting by city and park officials as it blocked views to the west, from the Concert Ground towards Sheep Meadow. Art Commission records indicate that city officials then settled on the hillside location for new design proposals.

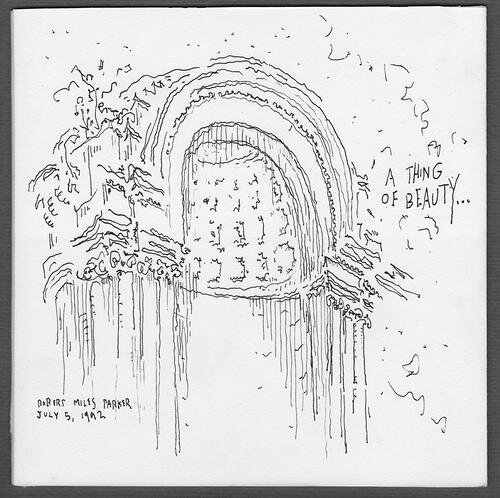

Elkan commissioned William G. Tachau, his nephew and an architect, to design a suitable structure. Tachau’s bandshell design, a half-sphere shape, faced with cast and Indiana limestone features was an innovation of its day. His prototype combined classical shapes and historic ornamental park building functions with an acoustically live and responsive stage. The bandshell form has since become a frequently used archetypal design for music pavilions, supplanting the earlier bandstand form. Conceived as a veritable ‘Temple of Music’, it fits into the European park structures that both Tachau and F.L. Olmsted, Central Park’s designer, would have studied. These date back to the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, when parks and gardens had ornamental temples, fountains and buildings devoted to a particular god, specific themes, subjects, or functions.

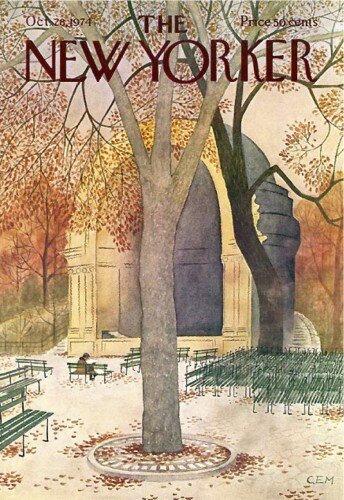

Though Central Park is largely composed of a series of informal landscape effects, the Mall, Concert Ground, and Bethesda Fountain precinct was originally conceived as a series of highly developed architectural, scenic, aural, and intellectual embellishments, many of which have since been lost and not reinstated. All were present when the Concerts began and Elkan’s provision of the Bandshell was agreed upon by the city. These included: an extraordinary vista from the Mall to the Belvedere Castle, to refresh the eye (now obscured by the Ramble’s canopy of untrimmed trees), a Ladies Refreshment Stand, later the Casino, to refresh the body (demolished-the site is now Rumsey Playfield), sprayer pools at the north end of the Concert Ground, to refresh the air and aurally and visually separate the Concert Ground from the cross-drive (now lost), a Literary Walk, to refresh the intellect by gently evoking poetry, literature, and history in the minds of visitors strolling under the elm tree canopy of the Mall in this idealized landscape (incomplete today), soft surfaces of grass and crushed gravel for both the Mall and the Concert Ground, to refresh the spirit by promoting quiet use of these spaces (now lost), and of course, music on the Concert Ground, to refresh the soul and mind with some of the Art’s greatest achievements (now severely curtailed in number by Parks policy and schedule restrictions).

The Naumburg Bandshell design has historic precedents for its shape in the Pantheon of Rome, or even more closely, in the Imperial Russian pleasure park’s pavilion at Gatchina Palace by Vincenzo Brenna–his ‘Eagle Pavilion’ of the 1790’s, and also in the later work of the architect F.G.P. Poccianti, particularly his ‘Cisternone’ at Livorno of 1829-42. It has historic precedents for its function in the outdoor theatres and pavilions of Versailles, for example, or the temples and ‘eye-catchers’ found in the park-like gardens of British country houses such as Stourhead and Stowe.

The half-domed design was chosen for the beauty of its line and for its acoustical properties. Embodying the highest achievement in the science of acoustics at the time, the Bandshell was innovative through its use of a double shell construction technique. The larger outer half-domed shell, and sixteen carved relief plaques visible from Rumsey Playfield and the wisteria pergola, is its weather shield. The smaller inner half-dome, consisting of a ceiling composed of interlocking coffered cast-stone panels, throws the sound out towards the audience.

Tachau, who graduated from both Columbia’s School of Architecture (1896) and the Ecoles des Beaux-Arts (1900), won both Gold and Silver Medals at the latter university. He then returned to New York and first set up the firm of Pilcher & Tachau and then Tachau & Vought. He went on to design three individually landmarked NYC buildings, in addition to the Naumburg Bandshell. Tachau, who joined the Concerts board, also continued to serve as the family’s architect, designing for them two family mausoleums, a triplex penthouse in the Hotel des Artistes (now transferred to the Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University), a country estate ‘Apple Bee Farm’ at Croton-on-Hudson, and other work.

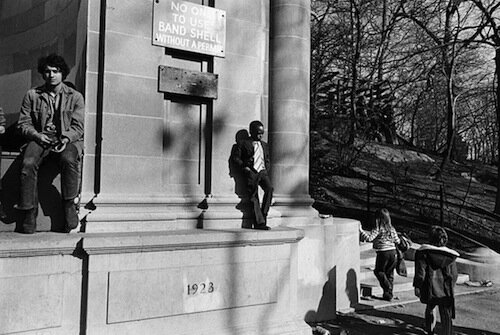

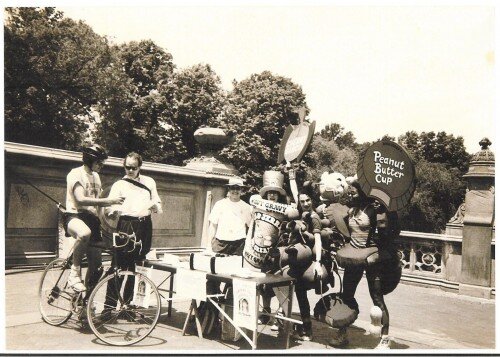

The Naumburg Bandshell was completed at a cost $125,000. Its engraved, and at one time gilded, inscription reads “Presented to the City of New York and its Music Lovers, Elkan Naumburg”. In 1989 it was threatened with demolition. Two separate and distinct proposals for change were objected to and thwarted. The struggle lasted four years. Many strongly disagreed with both of the proposed changes. The proponents of demolition were unresponsive to strong community board, public, and family objections. In response, the ‘Coalition to Save the Naumburg Bandshell’ was formed to rescue the building in 1991. Professionally an art and architectural historian, I led the effort. The Coalition fought a ‘last ditch effort’ with: radio ads and a WNYC interview, morning Channel 5 and New York One TV news appearances, widespread print and WPIX TV editorial support, 15,000 petition signatures, and a donated storefront office at 70th and Lexington Avenue. In 1992, a lawsuit filed against the Central Park Conservancy and the Parks Department rescued the Bandshell from imminent demolition. A decision on July 6, 1993 by New York’s highest court ended both the litigation and its planned elimination. This precluded the building’s removal and confounded the biased historic perspective of the Central Park Conservancy’s ‘vision’ for this area. I am most grateful to the people who aided this effort. In 2020 a renovation of the building was undertaken funded by a NYC Municipal grant, with additional funds from the Paulson Family Foundation and a substantial focused gift from Judith E. Naumburg to the CPC. The repair work was completed in June 2021. It addressed numerous difficulties with the building’s physical condition. The work shall hopefully encourage more use of this beautiful site, the Concert Ground, and the Bandshell, for music and other performances, going forward.

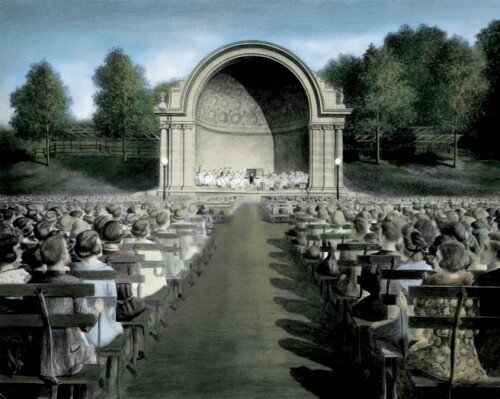

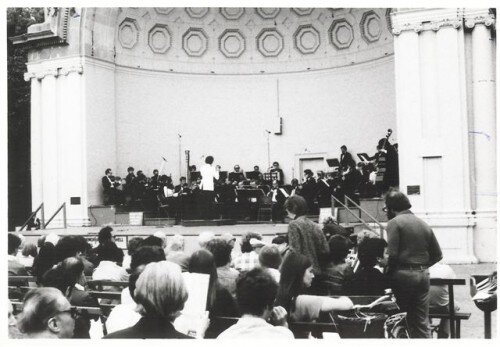

At the Naumburg Bandshell’s opening ceremony, on September 29, 1923, 3 p.m., Elkan was 89. Franz Kaltenborn led a 60-piece orchestra, with Katheryn Lynbrook of the Chicago Opera Company as the vocal soloist. 10,000 people attended the event:

The platform of the stand will accommodate seventy-five musicians, [with risers] and the shell, designed after consultations with specialists in acoustics, will distribute the music so that an audience of from 50,000 to 70,000 persons will be able to enjoy it, Mr. Goldman said.

– The New York Times, September 30, 1923

The opening concert consisted of selections from Aida, the Andante movement from Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, selections from Carmen, the William Tell Overture, the Blue Danube Waltz, and Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture. It ended with a now famous march, On the Mall, composed by Edwin Franko Goldman, who dedicated the piece to Elkan. In the summer of 1923 there were 959 free public concerts in Central Park, almost, and or more than double, those of the preceding two years. Some of this was attributed to the impending Silver Jubilee celebrations of the city. But today, there are far fewer concerts, and the bands and orchestras of New York have greater financial difficulty continuing their missions.

Elkan, the founder, first underwrote all costs for the Naumburg Concerts. When he died on July 31,1924, his sons Walter and George continued the Concerts until 1959, the year of Walter’s death. Walter’s will established a fund for the perpetuation of these Concerts, as long as they serve a public need and purpose. The Concerts have carried on principally through the support generated by this money. Unfortunately, that income is quite inadequate today so since about 1996, the Friends of the Naumburg Orchestral Concerts, along with foundation and corporate support, have significantly supplemented our budgets and program offerings.

Walter, whose musical philanthropies were spread among numerous institutions, included provision for Professorships of Music at Harvard, Rutgers, Brandeis and the New England Conservatory of Music and scholarship funds at Princeton and Juilliard schools of music. His other great contribution to music was the creation of the Walter W. Naumburg Foundation, which, through yearly competitions, launches the careers of young musicians with cash prizes and debut recitals. It also offers awards to chamber music groups and composers. Sometimes, the soloist performers the Concerts engage draw upon this considerable field of Walter W. Naumburg international competition prizewinners, a resource only begun and developed by Walter in 1926.

Two of Elkan’s other descendants also made significant contributions to the classical music world. His grand-niece, Eleanor Naumburg Sanger (1900-2000), and her husband Elliott M. Sanger helped co-found WQXR, now New York’s only classical music station. Eleanor served as WQXR’s music programmer from 1936 to 1960. Both Eleanor and her husband served on the Naumburg Concerts board for many decades with Eleanor’s brother, Ned [Edward S. Naumburg, Jr.]. Ned ran the concerts for over 25 years, retiring about 1980. Michelle R. Naumburg [George W. Naumburg, Jr. MD’s wife] then ran the concerts for ten years. In 1992, Dr. Christopher W. London [one of Elkan’s great-grandchildren] became President. This was largely the result of the first of three favorable court decisions to save the Naumburg Bandshell, granted to the Coalition to Save the Naumburg Bandshell, which he founded in 1990/91, to save the threatened building in Central Park. In addition, Elkan’s grandson Philip H. Naumburg (1920-95), was instrumental in founding the Santa Fe Chamber Music Festival in New Mexico. Philip also served on the Naumburg Concerts board, for over three decades, and now he is one of the Concerts Distinguished Benefactors.

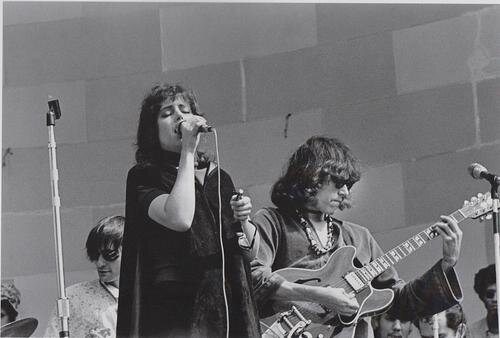

The Naumburg Orchestral Concert programs of the 21st century encompass a broad range of baroque, classical, romantic, and modern works. They are musically demanding, and entire symphonies and concerti are performed. There is an attempt to honor a 1938 Concerts Board decision, which announced that one piece of American music should be on each program. There is often contemporary music also included within the summer’s programs. They do not, as Walter often admonished, “play down” to the public. The Board of 1938 also wanted to “select soloists from the very large group of young talented native artists, whose opportunities to appear in public with an orchestra were limited.” The current Board continues to adhere to this policy too, as we feature promising new talent and we promote the professional development of young composers and conductors.

At the end of this booklet there is a compiled record of soloists and conductors who have performed for the Concerts over the last 100 years. The list contains many illustrious and distinguished names. It shows the Concerts were pioneers in bringing opera performances to Central Park. The roster also indicates that the Naumburg Concerts were early groundbreakers in presenting classical music opportunities to both African American and female soloists and conductors. We hope these previous efforts to innovate, and our present efforts to reinvigorate our series, will enable us to continue to appeal to the musical sophistication of our Central Park audience. The Board’s efforts and success with the Concerts were clearly still appreciated in the 1950’s. In a letter dated September 14, 1959, the then serving Parks Commissioner, Robert Moses wrote to George and Walter Naumburg:

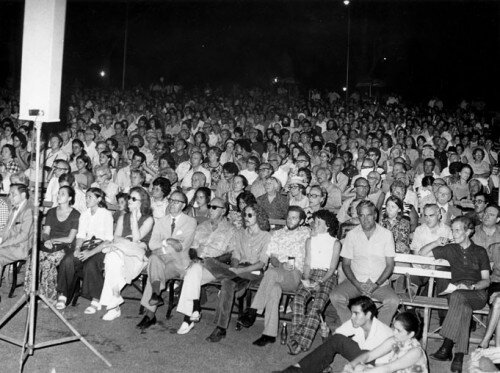

The Naumburg Symphony Concerts at the Mall in Central Park were again the major musical events of the outdoor concert season in New York City’s Parks. The public is always assured of excellent musical entertainment when the Naumburg programs are scheduled. They continue to attract thousands of listeners each evening.

I wish once again, to thank you and your brother for contributing these concerts. Your generosity is sincerely appreciated.

Since then, the most recent written acknowledgement from a sitting Parks Commissioner was August 19, 1977 from Joseph P. Davidson:

The value of the gift your family has so generously given to the City for so many years cannot be overestimated. These concerts have significantly enriched the quality of life in New York…

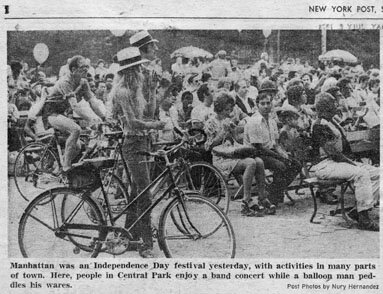

As we approach our eleventh decade, I hope that we can successfully continue Elkan Naumburg’s wish to provide the very best in free symphonic music to the public. Our audiences are certainly diverse, including serious music lovers who come from considerable distances; others hearing classical music for the first time; the typically “New York” mixture of various ethnic groups; as well as the bicyclists, joggers roller-bladers and dog-walkers who pause during their exercise to listen to Bartok, Beethoven, Bernstein, Dvorak, Haydn, Ives or Piazzola. But, I think anyone who attends our concerts must be amply rewarded when they see the rapt expressions of children hearing classical music for the first time; or an adult suddenly surprised by the immortal splendor of Mozart or Copland. All these things make our efforts worthwhile.

* * *

I want here to express my sincere gratitude to both the Naumburg Orchestral Concerts board and the Friends of the Naumburg Orchestral Concerts. Their generosity, coupled with the ongoing support of my family, has sustained and developed this enterprise over the last century. That combined and extraordinary devotion to this project, now for four generations of the Naumburg family, is what has kept Elkan’s vision alive. I also want to express my gratitude to the musicians, soloists and conductors, who over the years have endured; the sun in their eyes, the wind blowing the music off the stands, or the heat almost melting their precious instruments. The music union, Local 802 AFM also generously supported us for many years, in the past, with their Music Performance Trust Fund grants, helping us offset some of the costs of our series.

The Naumburg family’s love of music and their desire to share it with others has now been extended to many thousands of people over several generations. Elkan Naumburg’s foresight and Walter, Philip, Stephen, Michelle Naumburg and Ellin N. London’s generosity have helped ensure this tradition continues for New York’s music lovers of the future.

– Dr. Christopher Walter London (President, Naumburg Orchestral Concerts)